It’s one thing to feel ennui and crave the pursuit of true satisfaction, it’s another to relinquish job security altogether. What catalysed your decision?

One of my best friends, Sarah, whom I had known since I was fourteen, died at the age of thirty. She had cancer, which developed while she was carrying her first child. At the expense of her own life, she chose to delay treatment and carry her son to term. The doctor had to take her son out when he was just a seven-month-old preemie to try and save her with chemotherapy. But it was too late: the cancer had already metastasised. Seeing her on her deathbed was tough and painful. I was already into my third year of service, which met the minimum term of engagement. That was a rude awakening to stop wasting my life away.

Right after I left the army, I took a sabbatical and went to explore pottery routes in different countries, such as Taipei’s National Palace Museum where the Forbidden City collection is housed; Yingge Old Street, which is Taiwan’s pottery capital; Mashiko Museum of Ceramic Art in Haga District, Japan; and Raku Museum in Kyoto.

However, I didn’t plunge into the pottery business when my sabbatical ended. I went to work at my father’s construction business, where I was tasked with creating or amending two-dimensional construction drawings. It was during this time that I picked up the Computer Aided Design (CAD) software. Through experimenting with the three-dimensional (3D) aspect of the software, I discovered a neural-to-digital translation tool that could dually be used to express my artistic vision. It took me about four years to pick up the skill.

Construction drawings and pottery making are vastly different. How did you apply your 3D CAD skill for the latter?

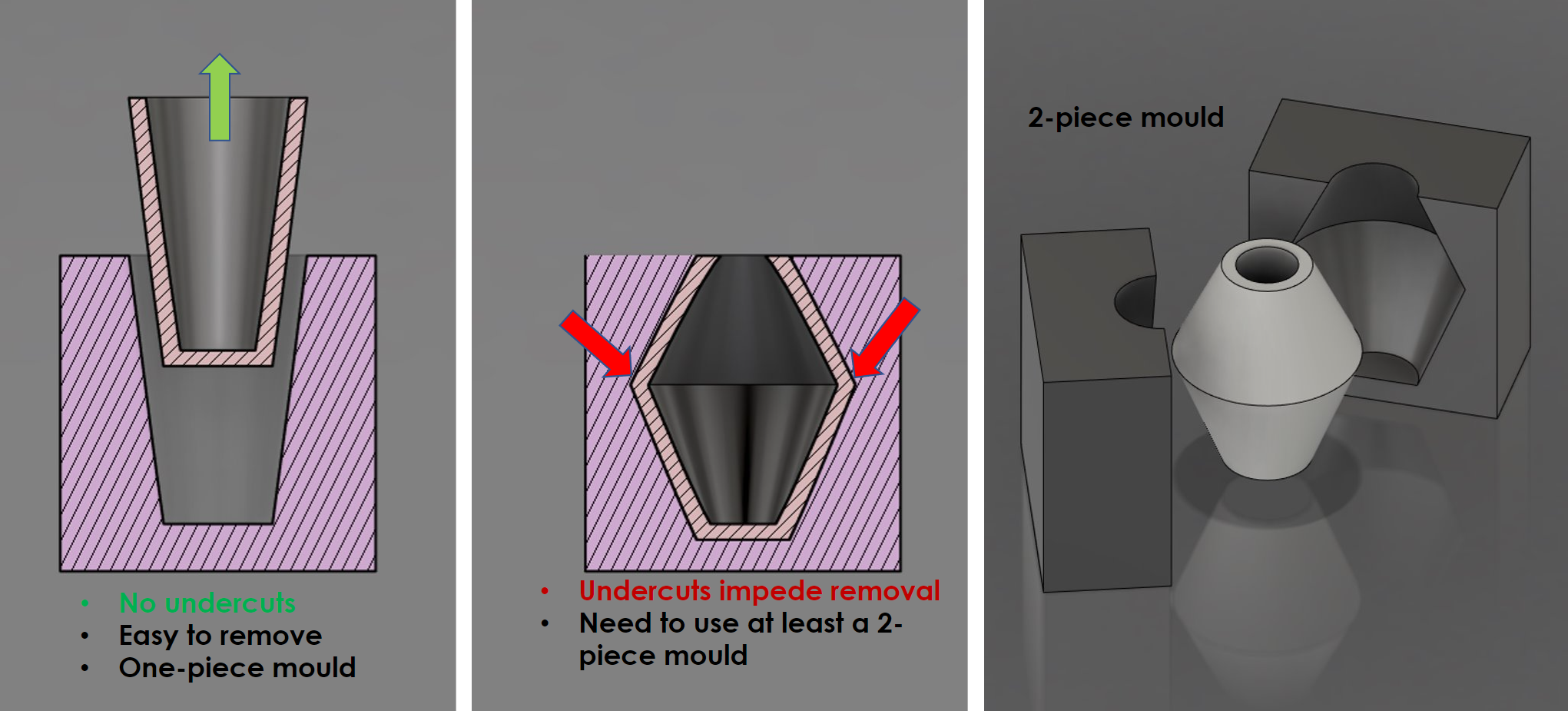

There are four main parts to my pottery-making process: designing, forming, glazing and firing. Designing includes the conception of the object itself — its function, proportions and aesthetics — which then gives shape to the mould of said object. Using 3D CAD software to design the mould gives me an advantage. Whereas a traditional mould-maker would have to depend on trial and error, I’m able to use the software to adjust and see the different angles of the mould. I don’t work in the dark and I can visualise the product. This is especially important, because I must be cognizant of the undercuts, which will hinder the smooth removal of the greenware. I like to call this a rendering of concepts into visible lines, shapes and shades: a neural-to-digital translation. The digital software brings to life ideas that hitherto are just electrical impulses inside my head.

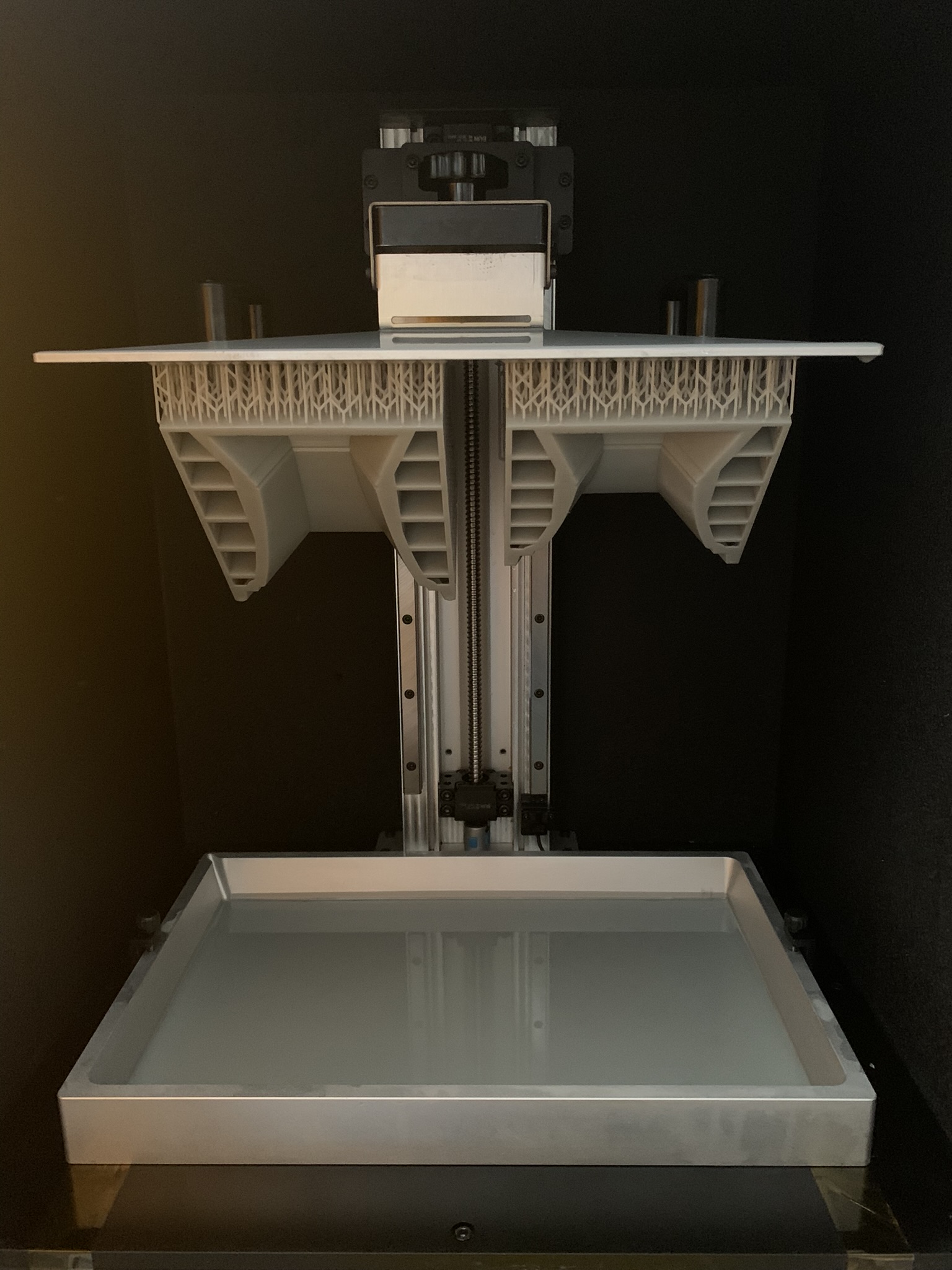

The next step is a digital-to-physical translation – where I use a 3D printer to materialise the model. This is where the rest of the process reverts to traditional hand methods.